What is Organic Chemistry?

Organic chemistry encompasses the scientific study of organic compounds, which are compounds characterized by the presence of covalently bonded carbon atoms. This field delves deeply into understanding the structural arrangements, chemical compositions, physical attributes, and chemical behaviors exhibited by these compounds. The profound impact of organic chemistry on society is evidenced by its pivotal role in the synthesis of various pharmaceuticals, polymers, and natural substances.

Initially, the term ‘organic’ was coined due to the belief that organic compounds were solely derived from living organisms, thus distinguishing them from inorganic compounds. This concept stemmed from the idea of a ‘vital force’ present in organic substances, which was thought to be absent in inanimate matter. However, this notion was challenged with the groundbreaking synthesis of urea by Urey and Miller from inorganic precursors, marking a significant shift in understanding. Despite this, the historical classification of organic compounds based on their origin persists in modern terminology.

The vastness of organic chemistry is attributed to a fundamental property of the element carbon known as carbon catenation. Carbon exhibits a remarkable propensity to form strong and stable bonds with other carbon atoms, enabling the creation of complex molecular structures. Catenation refers to the ability of an element to form bonds with atoms of the same element, and carbon’s unparalleled ability in this regard underpins the extensive diversity and complexity observed within organic chemistry. Thus, the richness and expansiveness of organic chemistry are inherently linked to carbon’s unique bonding capabilities.

The importance of organic chemistry in the present age is as immense as it has been since its inception. It plays an important role in our everyday life because food, medicines, paper, clothes, soap, perfumes, etc., are indispensable to us for proper living. The study of organic chemistry is important for chemists and pharmacists in synthesising medicines for the alleviation of human suffering.

The reactions in organic chemistry occur between organic compounds. Let us now study the different terminologies, classifications, field effects, types of reagents, the stability of intermediates, and properties in detail.

Cleavage of Bonds

The reactions in organic chemistry occur through the breaking and making of bonds. Bonds can cleave in either of two ways:

- Homolytic cleavage

- Heterolytic cleavage

What Is Homolytic Cleavage?

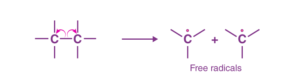

If the covalent bonds between two elements break in such a way that each of the elements gets its own electrons, it is called homolytic cleavage. That is, each element gets an electron. Homolytic cleavage results in the formation of free radicals.

Homolytic Cleavage of Covalent Bond

In the above figure, we have used an arrow to show the movement of electrons. Here, in this case, the arrow used is called the fish-hook arrow, as it signifies that there is a movement of only one electron.

In the above figure, we have used an arrow to show the movement of electrons. Here, in this case, the arrow used is called the fish-hook arrow, as it signifies that there is a movement of only one electron.

What Is Heterolytic Cleavage?

If the covalent bonds between two elements break heterolytically, i.e., unequally, it results in the formation of charged species. This type of bond breaking, where the electrons are unevenly distributed, is called heterolytic cleavage.

Heterolytic Cleavage of Covalent Bond

In the above figure, we have used arrows to signify the movement of electrons, a regular arrow signifies that two electrons are being moved.

Reaction Intermediates in Organic Chemistry

Intermediates can be understood as the first product of a consecutive reaction. For example, in a chemical reaction, if A→B and B→C, then B can be said to be the intermediate for reaction A→C. The reactions in organic chemistry occur via the formation of these intermediates.

What Are Carbenes?

Carbenes (H2C) are neutral and reactive species that have six electrons in the outer shell of carbon, making them electron deficient. Since carbenes are species having two odd electrons, we can classify carbenes based on their spin states.

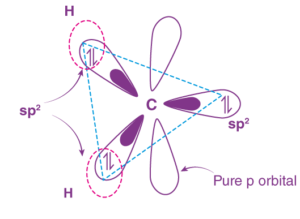

Singlet Carbene

The electrons are present in different orbitals with opposite spins. The electrons are paired in sp2 hybridized orbitals and behave as paired electrons.

Spin state= (2S + 1), S for singlet carbene is zero, as the electrons are antiparallel.

Therefore, spin state = (2 × 0 + 1) = 1

Triplet Carbene

Both electrons are present in different orbitals, and they possess the same spin.

Spin state = (2S + 1), S for triplet carbene is 1, as both electrons have the same spin.

Therefore, spin state= (2 × 1 + 1) = 3

Hybridization of Singlet and Triplet Carbene

Singlet carbene hybridization: They are sp2 hybridized with a bent shape. They have a bond angle of 103° and a bond length of 112 pm.

Hybridization of Singlet Carbene

Triplet carbene hybridization: They possess a sp hybrid orbital with a linear shape. They have a bond angle and bond length of 180° and 103 pm, respectively.

Why Is Triplet Carbene More Stable than Singlet?

Triplet carbene has lower energy than singlet carbene because, in singlet carbene, there are more inter-electronic repulsions as both the electrons exist in the same orbital, whereas in triplet carbene, the two electrons exist in different orbitals, making it possess less energy.

What Are Free Radicals?

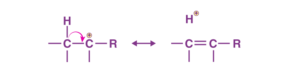

Free radicals in organic chemistry are formed by the homolytic cleavage of carbon bonds. The shape of the species formed is planar, and the carbon is sp3 hybridized with an odd electron being placed in the p-orbital. If the free radical is relatively stable, then it may possess a planar structure.

Planar Structure of Free Radicals

Carbanions and Carbocations

What Are Carbanions?

They are generated by heterolytically cleaving a group attached to carbon without removing the bonded electrons. This makes the carbon have a pair of electrons, thereby imparting a negative charge on the carbon. CH3– is isoelectronic with NH3, and it is sp3 hybridized, and the shape is pyramidal owing to the presence of a lone pair of electrons.

Formation of Carbanions and Carbocations

What Are Carbocations?

Carbocations have a sextet of electrons on the carbon-containing positive charge and are hence termed ‘cations’. It is sp2 hybridized and has an empty p-orbital. The shape is planar. It is generally formed by heterolytic cleavage of a carbon-heteroatom bond.

Transition State in Organic Reactions

We saw the intermediates that could be formed in an organic reaction; now, let us look into transition states and the difference between an intermediate and a transition state.

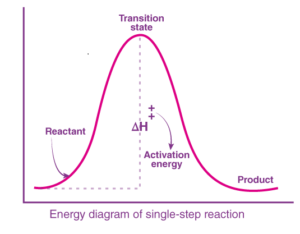

The intermediates in organic chemistry are formed in a multi-step reaction, but some reactions can occur in a single step without having to form an intermediate. These reactions will occur by going through a transition state. This can be clear by looking at the energy profile diagram for a reaction, R→P.

The transition state corresponds to the highest energy in the reaction, after which it can give either the products or, in the case of a reversible reaction, the reactants.

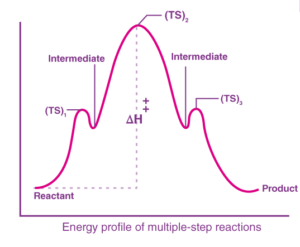

Consider a reaction, A→D with the following steps, A→B, B→C, and C→D

The energy profile for this reaction is given below:

We can see that B and C are the products of a reaction, and hence they are termed intermediates. The highest energy of a particular reaction should be the transition state.

Conclusion:

From the above example, we can show that the intermediates are isolable, that is, they can be isolated. On the other hand, the transition state is not isolable because we assume the reaction to take place via a transition state cannot be isolated.

Reagents in Organic Chemistry

Reagents are the chemicals that we add to bring about a specific change to an organic molecule. Any general reaction in organic chemistry can be written as follows:

Substrate + Reagent → Product

Where the substrate is an organic molecule to which we add the reagent. Based on the ability to either donate or abstract electrons, the reagents can be classified as follows:

- Electrophiles

- Nucleophiles

Electrophiles

Electrophiles are electron-deficient organic reagents. It can be generalised that all the positive charge-containing species are electrophiles. For example, H+, NO2+, CH3+, Cl+

Check: Electrophilic Substitution Reaction

Neutral molecules that are electron deficient can also act as electrophiles. Lewis acids like AlCl3 and BF3 are examples of neutral electrophiles.

Nucleophiles

Nucleophiles are electron-rich organic reagents. They seek bonding centres with other nuclei and hence the name nucleophile. It can be generalised that negative charge-containing species are nucleophiles. For example, H–, CH3–, and Cl–.

Neutral molecules with a lone pair of electrons on the heteroatom can act as a nucleophile. For example, H2O, NH3, and CH3OH.

Types of Reactions in Organic Chemistry

Organic reactions are reactions that occur between organic compounds. The reactions in organic chemistry are broadly classified into six categories. Let us study in detail these different types of reactions and their products.

Substitution Reactions

R-X + Y → R-Y +X

Where R-X is the substrate, Y is the reagent (which can be electrophilic or nucleophilic), and X is called the leaving group. The term substitution means one group is replacing the other group.

Types of Substitution Reaction:

- Nucleophilic Substitution ( SN1, SN2, SNi)

- Electrophilic Substitution (SE)

- Nucleophilic Aromatic Substitution (SNAr)

- Addition Reactions

Addition reactions can be further classified into:

- Electrophilic Addition

- Nucleophilic Addition

- Elimination Reactions

Elimination Reactions

These reactions can be said to be the reverse of an addition reaction, wherein a simple molecule (HX, H2O) is removed from the substrate, i.e., a molecule is said to be eliminated from the substrate. Elimination reaction can be classified further into E1, E2, and E1CB.

- Oxidation and reduction reactions

- Pericyclic reactions

- Molecular rearrangements

Field Effect in Organic Chemistry

Inductive Effect

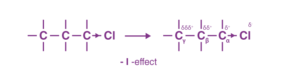

It is an electron delocalisation effect via σ bonds that arises due to the difference in electronegativities. For example, in a σ bonded organic compound like C-C-C-Cl, the carbon attached to the chlorine atom can be referred to as the α-carbon, and the one adjacent to that carbon as the ß-carbon and so on.

Now, since chlorine is more electronegative than carbon, it withdraws the electrons that are present via the σ bond toward itself, thereby making Cα fractionally positive. Since it is devoid of electrons, Cα, now being slightly electropositive than Cß, pulls the sigma-bonded electrons of Cα-Cß bond toward itself, and in this process, it makes Cß slightly electropositive.

The electron-withdrawing effect of the chlorine atom is transmitted through the carbon chain via the σ bonds. This transmission of charges decreases rapidly with the number of intervening σ bonds. We can practically ignore this effect beyond Cß.

The arrow is pointed more towards the electronegative atom. If a group withdraws the electron from carbon, it makes carbon slightly electropositive. Such groups are called -I groups, and the effect is termed -I effect. For example, -Cl, -Br, -CN and -NO2 are -I groups.

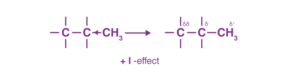

Groups that release electrons towards carbon are termed +I groups, and the effect is termed as +I inductive effect in organic chemistry. For example, alkyl groups like -CH3 are +I groups.

Electromeric Effect

It is the temporary delocalisation of π-electrons in a compound containing multiple covalent bonds. It is important to note that it is only a temporary effect, that is, it occurs only when a reagent is added. The Electromagnetic Effect in organic chemistry can be classified into two types:

- Positive Electromeric Effect

- Negative Electromeric Effect

Positive Electromeric Effect

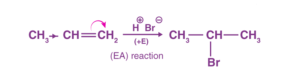

When the π-electrons are given to the attacking reagent, for example, the reactions alkenes and alkynes mostly occur via +E, this reaction is also called electrophilic addition.

Positive Electromeric Effect

The proton adds at C-1 as the π-electrons were given to the attacking reagent (H+). This results in the formation of a carbocation.

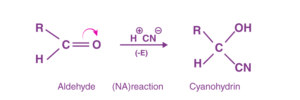

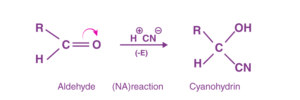

Negative Electromeric Effect

When the π-electrons are shifted to a more electronegative atom (O, N, S) joined via multiple bonds, it is called the negative electromeric effect. For example, the reactions of aldehydes and ketones occur predominantly by the -E effect. It is also called nucleophilic addition.

Negative Electromeric Effect

The CN- ion adds to the C atom of the carboxy group opposite to the movement of the π-electron cloud.

Mesomeric Effect

Molecules possessing sigma bonds and pi-bonds alternatively exhibit the mesomeric effect. The effect is exhibited due to the permanent delocalisation of π-bonds. This increases the number of resonating structures which makes the molecules of organic chemistry more stable. Such kind of a system, where there are alternative sigma and pie bonds, is called conjugated.

Types of Mesomeric Effect

- Positive mesomeric effect

- Negative mesomeric effect:

Positive Mesomeric Effect

This effect is exhibited when the direction of the delocalisation of electrons is away from the position where the group is attached. Normally, groups having a lone pair of electrons attached to a conjugated system push electrons into the conjugated system, that is, away from them.

Groups in organic chemistry showing positive mesomeric effect (+M) effect are -OH, -OR, -NH2, -SH, -X, etc.

Negative Mesomeric Effect

This effect is exhibited when the direction of the delocalisation of electrons is towards the position where the group is attached. These are generally electron-withdrawing groups of organic chemistry.

Resonance Effect

For certain molecules like carbonate ion (CO32-), one single Lewis structure would not be enough to explain all of the properties. In that case, the molecule is said to have more than one structure.

Each of those structures can explain some of the properties but not all of the properties. The actual structure of the molecule is a hybrid of all the possible structures (canonical forms). This phenomenon is called resonance in organic chemistry. If resonance occurs, each bond would be both a single bond and a double bond at the same time, i.e. the bond order would lie between one and two.

Resonating structures should fulfil the following criteria:

- All atoms should have the same positions in all the structures.

- There should have the same number of paired and unpaired electrons.

- The structures should have almost the same energies.

Note: Canonical forms do not have any existence in reality.

Resonance Energy

The energy difference between the most stable canonical form and the resonance hybrid is known as Resonance Energy. The more the resonance energy, the more the stability.

Rules for finding out the most stable canonical form:

- The canonical form with no charges is the most stable

- The canonical form with more number of covalent bonds is more stable

- The canonical form where unlike charges are in close proximity are more stable

- If they are to be charged, the negative charge should be on an electronegative atom. Then, this canonical form is said to be more stable.

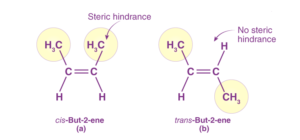

Role of Steric Hindrance

The structure and reactivity of many compounds in organic chemistry are greatly dictated by the presence of bulky groups or constituents in the molecule. This is called steric hindrance. It arises because of inter-electronic repulsions due to spatial crowding amongst bulky groups. Using steric factors, we can conclude that trans-2-butene is more stable than cis-2-butene.

Steric Hindrance in Organic Chemistry

Stability of Intermediates

Carbocations

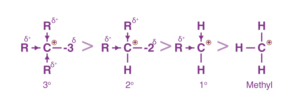

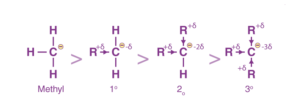

The stability of carbocations can be explained by the Inductive Effect.

CH3++CH2(CH3) +CH(CH3)2+C(CH3)3, i.e., Methyl Primary (1°) Secondary (2°) Tertiary(3°)

We know that alkyl groups of organic chemistry are +I groups, that is, they release electrons through the sigma bonds.

Since the carbon is deficient in electrons, we can say that as the number of methyl groups increases, the stability of the carbocation increases, as the electropositive carbon is satiated by the electrons given by the methyl groups via the +I effect.

Therefore, the stability order of carbocations in organic chemistry is of the order 3° > 2° > 1° > Methyl carbocation.

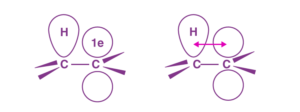

Hyperconjugation

When a C-H σ-bond is in conjugation with a carbocation, this effect is observed. A carbocation has a vacant p-orbital. The bonded σ-electron pair of the C-H bond is displaced towards the vacant p-atomic orbital. This increases the electron density in the empty p-AO.

It is, therefore, a resonance effect, where a C-H bond breaks and the σ-electron pair is delocalised to the vacant p-AO of the carbonation. Since the bond between C and H is broken, it is also called ‘no bond resonance’. It is also referred to as the Baker-Nathan effect.

The more the number of α-hydrogens in a carbonation, the more hyperconjugated structures would be possible. The more the number of structures, the more the stability of the species.

Stability of Carbanions

The stability of carbanions can be explained using the inductive effect.

CH3 — CH2(CH3) — CH(CH3)2 — C(CH3)3 i.e. Methyl Primary (1°) Secondary (2°) Tertiary (3°)

Since alkyl groups are electron-releasing by nature through induction, we can say that the more the number of methyl groups attached to the carbon having a negative charge, the less its stability would be.

This is because the carbon already has a negative charge, to which the methyl groups push electrons via induction. This results in inter-electronic repulsions and destabilises the species.

Therefore, the stability order for carbanions is as follows:

3°< 2°< 1°< Methyl carbanion

Stability of Free Radicals

The stability of free radicals in organic chemistry follows the same trend as that of carbocations.

CH3–CH2(CH3)–CH(CH3)2–C(CH3)3 i.e. Methyl Primary (1°) — Secondary (2°) — Tertiary(3°)

Therefore, the stability order of free radicals is of order: 3° > 2° > 1° > methyl carbocation.

This can be explained with the help of the Hyperconjugation that we saw, but there would be an overlap between the σ-bond of C-H and the odd electron in the p-orbital of carbon.

Note: If there is a possibility of resonance, then that would make it more stable. This is because resonance affects the entire structure.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the meaning of bond cleavage?

Answer:

The breaking of a chemical bond is called bond cleavage. There are two types of bond cleavage depending on the sharing of electrons between the two atoms of the bond.

1. Homolytic cleavage: The two electrons in the bond are equally shared between the two atoms.

2. Heterolytic cleavage: One of the atoms gets both the electrons of the bond.

2. What makes a strong nucleophile?

Answer:

The conjugate base of a good nucleophile. For example, OH– is a good nucleophile than H2O. The greater the negative charge, the atoms are more likely to give electrons to form a bond.

3. Is water (H2O) nucleophile or electrophile?

Answer:

Water is a highly polar compound with a high density of electrons or electron-rich molecules. Hence, water is an example of a nucleophile.